i

One of many issues with western classical music has been the gradual, but now pervasive de-risking of live performance. Today’s concert venue is not a place where we come to grapple with the unexpected or have our souls shaken to their very core. Your average symphony concert has become a figure skating exhibition. We collectively know, more or less, what is going to happen, which notes where and when, and how heartfelt or playful or just how impending this particular doom is. We know that we are witnessing something that is extraordinarily complex and difficult, we know that the people onstage have been training their whole lives for this, and we know the difference between sticking a landing and falling on your ass. That high-C coming up is a triple toe/triple axel combo and we will feel it all over, either way.

Pull back, and the range of outcomes, while microscopically infinite, are mostly pre-ordained and fall within a very narrow range.

“My, that Allegro was fast!”

“My, that Adagio was unbearably slow!”

It still is going to time out between 60-90 minutes with an intermission (because overtime), most of us will have the good sense to not clap in the messy bits (YOU WILL SOON LEARN THIS) and when we are bored we can mask it by glaring at candy unwrappers and iPhone lumiere-ists who we often secretly envy.

Because everyone must be paid, because banks and luxury cars need buyers, because we are so lazy and don’t want to watch anything that someone hasn’t already told us is wonderful (or at least that it really picks up in Season 2).

Because we can’t tolerate risk anymore.

Western classical music is supposed to be far more complicated than pop, but mind you don’t let it get too complicated. My litmus test: can you sing along with it, dance to it, or experience an enhancement to your chemically induced hallucinogenic state? Mild indifference is OK in mild doses, but strong negative reactions are a problem. Cracking open that door for new scales, new faces, new ideas is risky, and there is no room for risk anymore. Risk is a problem for box offices, for lonely luxury cars with lush leather interiors seeking drivers and, apparently, for people getting paid. Board man gets paid, or board man leaves town.

Like a proper glam rock band, the placecards stay in the same place with the same menu: lead guitar, rhythm guitar, bass, drums and sometimes nerd on keys, but in this case 16/14/12/10/8, 3+picc, 3+cor ang, 3+bass, 3+contra – 4, 4, 3+bass, 1, timp, 3perc, 2hp, pf/cel+nerd plus the occasional glass harmonica or cimbalom. If you don’t know how to write for these instruments or if your parents didn’t hand the RCM and Freddy Harris 5-10k a year for lessons, summer programs, exam accompanists and valve oil, this stage is not for you. Even you can see that it is too risky. Risk is for the lenders to assess when string players max their LOC for a perfect piece of pernambuco.

The violinist Mark Fewer once commented that he no longer enjoys going to professional concerts, because he already knows what will happen; student concerts, on the other hand, are way more unpredictable and interesting. Instead of making music more cozy, shouldn’t we be making it more uncomfortable? That uncertainty, like the first time you hear a symphony orchestra, the moments of having my mind blown, or being provoked into anger for non-political reasons, shouldn’t we try for more of this? Risk consistency over risk management? Personally, I worry when I don’t really want it, when I don’t want my cultural feedings to involve struggle or pain or to leave me feeling stupid. By adding risk, you risk alienating your audience, or so goes the mantra of the prudent programmer.

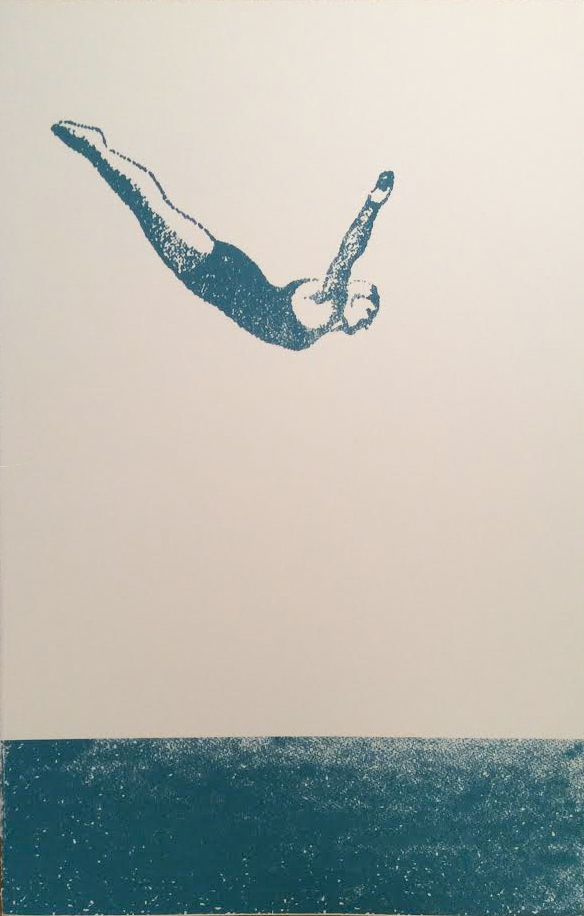

The darker side of prudence, of fiscal common sense, is really dark. Every season there we celebrate a dead white male milestone – Beethoven’s 200th deathiversary (not yet), Mozart’s 275th Birthday (not yet), the 5th anniversary of the end of blackface in opera (not yet). The 1st anniversary of the TSO festival giving space to an IBPOC festival? Yeah. Giving space is risky. Yet, to paraphrase my colleague Neema Bickersteth, risk in the form of danger is what makes roller coasters fun, and risk in the form of faith is what gives value to believing in something bigger than yourself, and going out on a limb and creating art means trusting in something unknowable. De-risking art risks the art itself.

ii

A touring production of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton recently opened in Toronto, a phenomenon that anecdotal scientists confirm has captured more hearts from more demographics than any show since West Side Story. It is also notorious for the massive markups from ticket resellers, because the demand for the scarce ticket supply is so high.

The difference between “commercial” musicals and “high art” operas and symphonies is supposed to be the singular pursuit of artistic excellence and purity of intention upheld by the latter. It is also the difference between shows that make money and shows that take money – organizations subsidized through public funding like the Canada Council, OAC or TAC. Digging deeper within the genetics of high art reveals some unsettling connections.

If you are an artist trained in a western classical tradition, think of some of these characteristics:

perfectionism, a sense of urgency, worship of the written word, belief in one right way, individualism, a belief that I’m the only one who can do this right, a belief that progress is bigger and more, a belief in objectivity.

To me, some of these read like a list of conservatory training virtues, yet Tema Okun, in her written work available on dismantlingracism.org, lists these as some of the characteristics of white supremacy culture.

“Culture is powerful precisely because it is so present and at the same time so very difficult to name or identify. The characteristics listed below are damaging because they are used as norms and standards without being pro-actively named or chosen by the group and because they promote white supremacy thinking and behavior.”

https://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/

It rings true, and it rings scary – our diligent pursuit of olympic perfection, the industry of authenticity, veneration of muscular virtuosity and our singular devotion to continental Euro-culture as the divine.

Quick – name the last piece the TSO programmed by a Canadian composer that took up at least half the program.

Now name one from a person of colour. Now name two.

Now as I rush to cover my ears amidst the verbal hubbub of justifications, I’ll point out the latest newsletter from Soulpepper, Toronto’s largest classical theatre company. Thanks partly to the leadership shown by companies like Obsidian Theatre, and partly to the leadership shown by…their leadership, this is an example of things getting better. Things can get better. We can have large arts organizations that don’t impersonate pop-up European cultural embassies.

Meanwhile, when Volcano Theatre in Toronto did all the heavy lifting in a reworking of Scott Joplin’s opera Treemonisha, assembling a great and predominantly black female cast and creative team, they were not able to secure a Canadian presenter. Too risky? Not able to clear the lofty

bar set by the likes of Johann Strauss, Engelbert Humperdinck and Rufus Wainwright?

So Hamilton, the commercial show, makes money and teaches life lessons to a pan-cultural spectrum of youth, allowing them to see people that look like them on the big stage (it matters). High-art large organizations that champion openly racist and misogynistic work are heavily subsidized. Don’t worry though – they are actively involved in outreach:

“[Alexander Neef] says what he thinks and is very involved in building a younger audience for opera,” says Trinity Jackman, a COC board member who chairs the Ensemble Circle, a group of mostly young patrons whose Operanation event two years ago included COC Ensemble members singing with Broken Social Scene.”

(Robert Everett Green “How Canadian Should the Canadian Opera Company Be?” Globe and Mail, April 9, 2012)

Meanwhile, relatively miniscule organizations are finding ways to do the work that actively tries to include all Canadians, with budgets that a house of cards would feel sorry for.

Here’s my disclaimer, conveniently nestled at the end of what started as a Facebook post and turned into a slightly unhinged rant. I am conservatory trained, and I have made a living, at least until COVID-19, as a western classical musician working with organizations like the COC and TSO, as well as many other privately and publicly funded organizations.

“Those Oriental people work like dogs … they sleep beside their machines,” he said. “The Oriental people, they’re slowly taking over … they’re hard, hard workers.” – Rob Ford

Armed with broad-spectrum white approval, Asians, sans Asian culture, are not unusual to see in the mainstream classical music world. I have never felt the barriers that IBPOC people have candidly and repeatedly identified when discussing their experiences and interactions with Eurocentric organizations. (see #inthedressingroom on Twitter)

So here are some of the questions I have been struggling with amid the most recent outrageous racist events.

To the public funders – what are the values you are rewarding when you generously fund organizations who not only have a history of excluding “others”, but have the values of exclusion written into their very DNA? Rather than try to remake the stubborn, can we prioritize what and who we are supporting? How much do we value equality?

To private funders – I get it, but I wish it were otherwise.

To the big classical organizations, first a request. Stop posting about the healing and transformative power of classical music and its ability to solve all problems (physician, heal thyself). Also, when building bridges to other cultural groups, and teaching them to appreciate and embrace your traditions, remember to allow oncoming traffic. Finally, I’d like to share some words by Aria Evans in a recent Dance Current article:

Ask yourselves: are you afraid to lose donors? Is money more important than human life? Is that colonial, capitalist value something you truly want to stand behind? You have the potential to use your platform to inform and enlighten. It’s not about pushing an agenda onto audiences, it is about upholding the notions of equality.

That last sentence hits hard. Is equality important to you? How important – I mean, how many dollars is equality worth?

Finally, to my colleagues and friends, some of whom I cannot imagine do not hold me justifiably in some level of contempt. I know this is possibly the worst time in our lifetimes, maybe even those of our parents, to contemplate opening up, and inviting in, and possibly giving up things. I know many of us feel we literally cannot afford to. I invite all of us to really think about what we cannot afford to do. What is equality worth?